EIGN SEWAGE TREATMENT WORKS AND THE HISTORY OF SEWAGE IN HEREFORD

You might be forgiven for wrinkling up your nose as you walk through Bartonsham and smell the sewage treatment works or as you catch a whiff of sewage when cycling across the Greenway. Maybe you feel that the treatment works are rather close to the city but how good to know that this area has effectively “taken one for the Hereford team” for 165 years by giving a home to the Eign works.

By the 17th century Hereford was past its prime, it was poverty stricken and keeping the wells and pumps clean was impossible with residents, “emptying pissepots and other stinking excrements to ye greate annoyance of the neighbours” There was little that the Council could do as living conditions became more squalid and a privy was shared between many houses usually just emptying into a cesspool, a boghole or the cellar. You could pay the “night soil” man to empty it, at night between midnight and 6am, or just dig another hole.

Typhus, diarrhoea, smallpox and typhoid were common and life expectancy was short. Luckily cholera did not reach the city in the mid 19th century but turned out to be the “best of all sanitary reformers”

In 1853 Thomas Rammell, inspector, conducted a 4 day inquiry in Hereford into sewerage, water, burial grounds and sanitary conditions. Although chest diseases, TB and pneumonia, led to more deaths than infectious diseases no-one questioned them and the recommendations were based on sanitary conditions. The inquiry found that:

- public wells were now only available for fire-fighting, the water coming from them was hard and not good for soap economy plus river water at a ha'penny a bucket was soft, made a good cup of tea and made tea leaves go much further

- most cesspools were above the well level and likely seeped into the well water

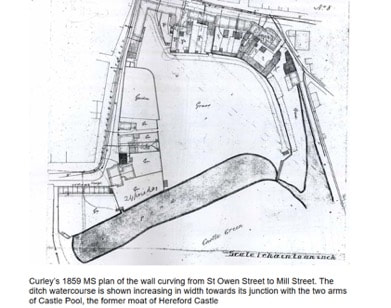

- drains discharged directly into brooks but the Castle mill pond and moat was “the most glaring evil” with poor houses and St Owen's overflowing burial ground adjoining

- outbreaks of typhus, diarrhoea, scarlet fever and small pox were partly attributed to “emanations from the pond” (remember this was before John Snow's discovery that cholera was caused by polluted drinking water and not from the miasma of bad smells)

- Hereford also boasted :– slaughterhouses adjoining all butcher's shops, leather currier's in Maylord, weekly cattle market in the centre, candle makers in West Street where fat deposited in the tallow warehouses on Saturday stank abominably by Monday so local fishermen could collect their maggots at the beginning of the week

- burial provision could have been improved in the 18th century if the bishop hadn't stopped a 6 acre site at Broomy Hill being used as it would “alienate the landed property of the see”!!

(1(The council did act quickly and in 1854 appointed Timothy Curley, civil engineer, to carry out the recommendations of the inquiry. Curley's map and plans, including the drainage plan for the city, can be seen in the Town Hall behind the stairs. He was very blunt:

“I witnessed such scenes of filth and uncleanliness in this city, as I did not before believe could exist in a civilised community..the floors of several privies being inundated by the semi-fluid contents of the cesspools; in some cases they are too filthy to be entered.”

Curley's plan included sewers to drain every house and with the ability to be extended, sewers to be self cleansing and with the outfall removed as far as was practical from the town with “manure tanks”for settling the solids. Plenty of the city sewage, now drained from houses, was discharged into the Wye, it wasn't until 1970s that all discharging of untreated sewage was finally stopped. Where was as far as practical from the town? Well that's where Bartonsham comes in, in 1885 work started on the sewage treatment works at Eign.

Steam driven pumping plant

The layout of the site can be seen in the 1931 map of the ecclesiastical parish of St James, here.

After the Second World War work began on a new sewage works to serve a population of 50 000. A complete photo record of the four year build from 1948 to 1952 is held at HARC (1) and provides evidence of some of the changes to the river that came about through the project:

Here is a link to our Stories tab > Places; for pictures of construction of the sewerage bridge between Bartonsham and Rotherwas. Posted by Angie Morris-Harman

(1) The Hereford Archive and Record Centre have three photo sources – a photograph of the sewage works before the post war works took place, two albums charting the progress of the build on the 1948 – 1952 project and aerial photos of the sewage works from 1952.

“I witnessed such scenes of filth and uncleanliness in this city, as I did not before believe could exist in a civilised community..the floors of several privies being inundated by the semi-fluid contents of the cesspools; in some cases they are too filthy to be entered.”

Curley's plan included sewers to drain every house and with the ability to be extended, sewers to be self cleansing and with the outfall removed as far as was practical from the town with “manure tanks”for settling the solids. Plenty of the city sewage, now drained from houses, was discharged into the Wye, it wasn't until 1970s that all discharging of untreated sewage was finally stopped. Where was as far as practical from the town? Well that's where Bartonsham comes in, in 1885 work started on the sewage treatment works at Eign.

Steam driven pumping plant

- five precipitating tanks

- night flow storage tanks

- 6.5 acres of filter beds

- sludge compacted in 2 filter presses and afterwards tipped onto the site

- in 1897 a refuse burner was added and produced a reduction in the site coal bill

The layout of the site can be seen in the 1931 map of the ecclesiastical parish of St James, here.

After the Second World War work began on a new sewage works to serve a population of 50 000. A complete photo record of the four year build from 1948 to 1952 is held at HARC (1) and provides evidence of some of the changes to the river that came about through the project:

- initial excavation of the site was followed by substantial flooding in the first weeks

- subsequently the river was dredged to reduce the chance of the site flooding – a photo shows lorries in the river by the old ford which was removed by dredging

- a large embankment was built up to protect the site from future flooding

- the outfall dam is made of copper with the more erodible pipes protected inside

- the gravel bank near the outfall was formed by the culvert apron and the copper outfall dam.

Here is a link to our Stories tab > Places; for pictures of construction of the sewerage bridge between Bartonsham and Rotherwas. Posted by Angie Morris-Harman

(1) The Hereford Archive and Record Centre have three photo sources – a photograph of the sewage works before the post war works took place, two albums charting the progress of the build on the 1948 – 1952 project and aerial photos of the sewage works from 1952.

Sewage treatment works in Britain from Above 1952

https://britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EAW046838

Finally plans drawn up in 1963 proposed that future sewage and storm water needs be met by piping most of the dry weather sewage to a site in Rotherwas. The work on the new plant and pipe line was started in 1978.

https://www.herefordshirehistory.org.uk/archive/herefordshire-images/aerial-views-of-herefordshire/aerial-views-of-hereford/river-wye-flooding-in-hereford-december-2000/1207689-hc026-river-wye-flooding-in-hereford-december-2000jpg?

And here is a picture of the flooded Wye from 2000 showing the upgraded works and the pipeline.

https://britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EAW046838

Finally plans drawn up in 1963 proposed that future sewage and storm water needs be met by piping most of the dry weather sewage to a site in Rotherwas. The work on the new plant and pipe line was started in 1978.

https://www.herefordshirehistory.org.uk/archive/herefordshire-images/aerial-views-of-herefordshire/aerial-views-of-hereford/river-wye-flooding-in-hereford-december-2000/1207689-hc026-river-wye-flooding-in-hereford-december-2000jpg?

And here is a picture of the flooded Wye from 2000 showing the upgraded works and the pipeline.

The water cycle provided by Thames Water

1. Taking the wastewater away

When you flush the toilet or empty the sink, the wastewater goes down the drain and into a pipe, which takes it to a larger sewer pipe under the road.

The sewer then joins our network of other sewers and takes the wastewater to a sewage treatment works - sometimes it needs to be pumped there.

At the sewage works we put the wastewater through several cleaning processes so that it can be put back safely into rivers.

2. Screening

· The first stage of cleaning the wastewater is to remove large objects that may block or damage equipment, or be unsightly if allowed back into the river. This includes items that should never have been put down the drain in the first place - such as nappies, face wipes, sanitary items and cotton buds - but often can be things like bricks, bottles and rags!

- The wastewater often contains a lot of grit that gets washed into the sewer, so we have special equipment to remove this as well.

3. Primary treatment

The wastewater still contains organic solid matter - or human waste. The next stage is to seperate this from the water, and to do this, we put the wastewater into large settlement tanks, which causes the solids to sink to the bottom of the tank. We call these settled solids ‘sludge’.

In a circular tank, large arms, or scrapers, slowly move around the tank and push the sludge towards the centre where it is then pumped away for further treatment.

The water passes over a wall near the top of the tank and is taken to the next stage of the treatment process.

4. Secondary treatment

Although the visible bits of sludge have been removed, we have to ensure that the smaller and sometimes invisible nasty bugs are also taken out.

At our larger sewage treatment works, the wastewater is put into rectangular tanks called ‘aeration lanes’, where air is pumped into the wastewater. This encourages the good bacteria to break down the nasty bugs by eating them.The more they eat, the more they grow and multiply until all the nasty bugs have gone.

5. Final treatment

The treated wastewater is then passed through a final settlement tank, where the good bacteria sink to the bottom. This forms more sludge - some of it is recycled back to the ‘secondary treatment’ stage, and the rest goes to ‘sludge treatment’. The now clean water passes over a wall near the top of the tank.

Sometimes additional treatment is needed if the river that the treated wastewater will be returned to is particularly sensitive. The treated wastewater is slowly filtered through a bed of sand, which acts as a filter and catches any remaining particles.

6. Sludge treatment

The sludge we collect at the start of the process is then treated and put to good use. Most of it is recycled to agricultural land for farmers to use as fertiliser, but we also use it to generate energy. We do this in three ways:

· Combined heat and power - this process treats the sludge using a process called ‘anaerobic digestion’. This is where the sludge is heated to encourage the bacteria to eat it. This creates bio-gas that we then burn to create heat, which in turn creates electricity.

· Gas to grid - we can also clean the bio-gas to a higher standard (known as biomethane) so that we can put it into the national gas grid to power homes, businesses and schools.

- Thermal destruction - this process involves drying the sludge into blocks called ‘cake’, which are then burned to generate heat. We capture this heat and turn it into electricity.

Now the wastewater is clean, it can be returned to local rivers and streams. In some areas, the water we put back into the river is very important as it helps to keep them healthy.

The quality of the cleaned wastewater is strictly regulated by the Environment Agency, and we test it to make sure that it meets high-quality standards.

…..but what about the withies?

We know that the withy or willow bed at the most southerly point of the bend belonged to the sewage works. Here's the evidence, taken from previous research by the History group:

At their conference in May, and after their meatless meal at the Green Dragon and a visit to the city sewage works (much admired for its efficient system which included the growing of withies that were made, on the premises, into the corporation’s fruit baskets), (Institute of Sanitarly Engineers in a meeting with Hereford Council in 1918)

So far I have been unable to find out why the sewage works planted the withy bed. Was it to filter the water that went back into the Wye, taking out the nitrogen? The cleansing properties of reed beds have been known for centuries but the use of willow would appear to be a more modern phenomena. Welsh Water are trying to find out on our behalf as are Hereford Nature Trust but neither have the answer yet. The mystery continues.