Bartonsham's Historic Mills

This article by Huw Rees, Andy Tatchell, Tony and Rosi Taylor, Julie Orton-Davies and Bill Laws, originated from BHG’s Mills Walk in December 2016. It was devised by Huw Rees: “While we spent many hours using the excellent resources at Herefordshire Archive and Records Centre, pillaging the internet, raiding our bookshelves and picking each other’s brains over beers and coffees, we do not claim that these notes are definitive, complete, or even accurate. We do hope however that you will find them of interest and will join us to contribute your own insights.”

The use of water power to grind corn was pioneered by the Romans and probably brought to Herefordshire in the first century. By medieval times the local mill was well established as part of the fabric of feudal society with the landlord requiring all his tenants to use his mill to grind their corn. Water mills were at the cutting (or grinding) edge of technology and required experienced skills to build and maintain. They were used for other purposes such as fulling cloth and forging iron and in Hereford in the late middle ages there were probably up to ten mills in operation. Yet mills are generally ignored by historians who focus on the grand sweep of history rather than fundamental issues such as how the key ingredient for daily bread is sourced.

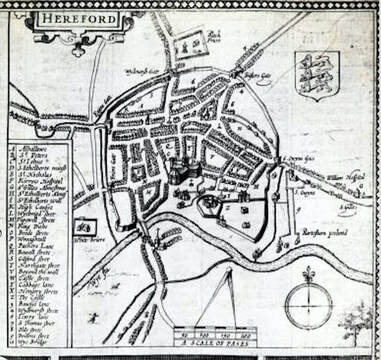

This information on the local mills is buried in the dry and dusty world of accounts, rent rolls and lease renewals, although many map makers have enlivened parts of their maps to draw mills, particularly in towns and cities.

The use of water power to grind corn was pioneered by the Romans and probably brought to Herefordshire in the first century. By medieval times the local mill was well established as part of the fabric of feudal society with the landlord requiring all his tenants to use his mill to grind their corn. Water mills were at the cutting (or grinding) edge of technology and required experienced skills to build and maintain. They were used for other purposes such as fulling cloth and forging iron and in Hereford in the late middle ages there were probably up to ten mills in operation. Yet mills are generally ignored by historians who focus on the grand sweep of history rather than fundamental issues such as how the key ingredient for daily bread is sourced.

This information on the local mills is buried in the dry and dusty world of accounts, rent rolls and lease renewals, although many map makers have enlivened parts of their maps to draw mills, particularly in towns and cities.

The mills of Mill Street

Mills Street was home to at least three mills, all supplied with water from the city ditch or castle mote, which was fed from Yazor brook. The upper mill was Dog Mill, (situated around No 9 Mill Street). Dog Mill appears on Speeds map of 1610, as does The Castle Mill which stood on the site of the Hospital Lodge. The Castle Mill also appears on Taylor’s map of 1754, but the Dog Mill is not longer evident on this map.

There was also a St Guthlac Mill described as being sited somewhere below Hereford castle and having been destroyed by Roger de Mortimer in 1264 and rebuilt by 1320. This may have been the predecessor of Castle Mill.

More mills, located on Bartonsham Meadows, drew their water from a stone fish weir situated just below Victoria Bridge. These Hereford Mills were owned by the Dean and Chapter of Hereford Cathedral and they continued grinding corn after Henry VIII succeeded to the English throne in 1509.

When the King appointed himself head of the English church (in order to dispose of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and marry his second, Anne Boleyn) the nation broke away from the Roman Catholic church. Yet the Hereford Dean and Chapter continued to tolerate its Catholic priests and hold feast days. It was an unwise move: angered by their papist tendencies the King, in 1527, ordered the Hereford Mills to be demolished and the resulting hardship was only relieved when, in 1555, Queen Mary and Philip introduced the Hereford Mills Act empowering the Dean and Chapter to rebuild the mills along with fishing rights and two tow paths that led to the mills.

These mills ceased operation in the early 1700's when the weir on the Wye was demolished, to allow free navigation of the river up to Hereford. At that time the complex had three corn mills and three tucking mills and their closure brought extra business to the Eign Brook mills .

By the mid 1800s the Mill Street millpond was filled in, Castle mill had been demolished and the site, purchased by a Mr Edwards, was turned into a vegetable garden and orchard. The ground later became a children’s playground, although in 1887, after complaints from residents, it was turned into the parkland we see today.

In 1886 Cantilupe Street was built; in 1893 the river walk was constructed and in 1897 the Victoria Bridge was built to mark Queen Victoria’s Jubilee.

There was also a St Guthlac Mill described as being sited somewhere below Hereford castle and having been destroyed by Roger de Mortimer in 1264 and rebuilt by 1320. This may have been the predecessor of Castle Mill.

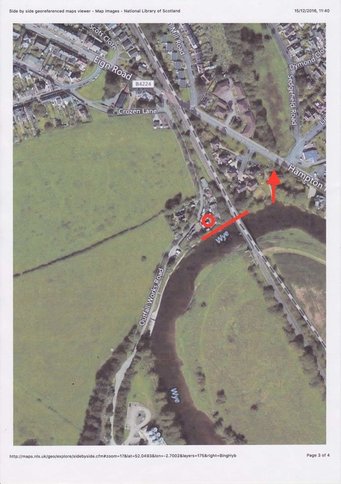

More mills, located on Bartonsham Meadows, drew their water from a stone fish weir situated just below Victoria Bridge. These Hereford Mills were owned by the Dean and Chapter of Hereford Cathedral and they continued grinding corn after Henry VIII succeeded to the English throne in 1509.

When the King appointed himself head of the English church (in order to dispose of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and marry his second, Anne Boleyn) the nation broke away from the Roman Catholic church. Yet the Hereford Dean and Chapter continued to tolerate its Catholic priests and hold feast days. It was an unwise move: angered by their papist tendencies the King, in 1527, ordered the Hereford Mills to be demolished and the resulting hardship was only relieved when, in 1555, Queen Mary and Philip introduced the Hereford Mills Act empowering the Dean and Chapter to rebuild the mills along with fishing rights and two tow paths that led to the mills.

These mills ceased operation in the early 1700's when the weir on the Wye was demolished, to allow free navigation of the river up to Hereford. At that time the complex had three corn mills and three tucking mills and their closure brought extra business to the Eign Brook mills .

By the mid 1800s the Mill Street millpond was filled in, Castle mill had been demolished and the site, purchased by a Mr Edwards, was turned into a vegetable garden and orchard. The ground later became a children’s playground, although in 1887, after complaints from residents, it was turned into the parkland we see today.

In 1886 Cantilupe Street was built; in 1893 the river walk was constructed and in 1897 the Victoria Bridge was built to mark Queen Victoria’s Jubilee.

Eign Mill, Eign Road

The date of the founding of the first mill on Eign Brook (its former entrance was Eign Mill Road) is unknown. Taylor’s map is the first that shows it and the mill is mentioned in the Grants of Mills of 1538-1594 . It may have existed before then.

The when is perhaps not so important as the where. Looking at Eign Brook, even on a winter’s day, it is difficult to see how the brook could provide enough water to power one mill, let alone the three others upstream: Scutt Mill in Ledbury Road, Monkmooor Mill sited where Morrisons is today and Widemarsh Mill just off Edgar Street. Building water mills on the River Wye was not an option, unless, like the Hereford Mills (see below) they were protected by a fish weir. Otherwise they risked being washed away.

On the Brook, however, water flow could be regulated with mill ponds to store water during the summer. Maps such as Curley’s of 1858 show extensive mill ponds for each of the four Eign Brook mills; Eign Mill’s is shown as extending up the valley almost as far as the Ledbury Road. Also the flow of Eign brook was stronger when it drained Widemarsh, the aptly, if a little unimaginatively named, wide expanse of marshy ground outside the City walls, and carried away surface water which, these days is intercepted by culverts. (It is said that in Saxon times, there was even boat building on the banks of Eign Brook.)

It is also possible that the Yazor Brook, which now runs parallel to Eign Brook for part of its course, could have been a tributary of Eign Brook. Yazor Brook had been diverted to power the Eign Gate Mill situated west side of the City on the corner of what is now Bewell and Victoria Streets.

The Eign Mill, clearly a significant mill during the 19th century, was improved in 1814. It had two water wheels powering six sets of French stones, a dressing machine and a bolting mill (used for grading and separating the flour and bran). About this time, the mill was leased by the James family, including Philip Turner James and, from 1830, Isaac William James. We know more about Isaac than the other millers listed in the Littlebury’s directories of this period, because of a collection of documents at Herefordshire Archives and Records Office (HARC) apparently collected by the Trustees of Isaac’s estate. Isaac was parted from his fortune and declared bankrupt in February 1867. His fall from grace was fast. He was listed as miller and maltster in 1830 and in the 1867 trade directory (presumably compiled in 1866) he was a maltster, agent for seeds, manure etc. with offices in Maylord Street. He was also listed as a farmer at Eign Farm at Tupsley. The Bartestree section of the Littlebury directory lists Isaac James as a farmer and hopgrower living at Bartestree Court. He appeared to live well - there is a bill from a Gloucester wine merchant dated 1863 for two dozen bottles of finest claret, costing £4 18 shillings, including carriage to Barrs Court Station.

The cause of his bankruptcy is not known, but he incurred a number of big bills in repairing and upgrading both Eign and Scutt mills, which appear to be steam powered. There are bills dated 1865 for £24 (the equivalent of 140 bottles of finest claret) for repairs to engine and boiler at Eign Mill payable to a Shropshire engineer as well as numerous bills to local metal fabricators.

The conversion to steam and its associated costs were probably forced on Isaac because of increasing competition. The Corn Laws, which limited the import of cheap wheat from the US, Canada and Australia, were repealed in stages from 1846 and, with coming of the railways to Hereford a few years later, would have brought cheaper grain to Hereford where purpose-built steam mills such as the Imperial (below) and two other modern mills, the Victoria and the Hereford, could undercut the domestic product. There are no further references in the trade directories to either Isaac or Eign Mill and the 1888 Ordnance Survey map shows the mill as derelict. It disappears totally in the 1904 edition.

The when is perhaps not so important as the where. Looking at Eign Brook, even on a winter’s day, it is difficult to see how the brook could provide enough water to power one mill, let alone the three others upstream: Scutt Mill in Ledbury Road, Monkmooor Mill sited where Morrisons is today and Widemarsh Mill just off Edgar Street. Building water mills on the River Wye was not an option, unless, like the Hereford Mills (see below) they were protected by a fish weir. Otherwise they risked being washed away.

On the Brook, however, water flow could be regulated with mill ponds to store water during the summer. Maps such as Curley’s of 1858 show extensive mill ponds for each of the four Eign Brook mills; Eign Mill’s is shown as extending up the valley almost as far as the Ledbury Road. Also the flow of Eign brook was stronger when it drained Widemarsh, the aptly, if a little unimaginatively named, wide expanse of marshy ground outside the City walls, and carried away surface water which, these days is intercepted by culverts. (It is said that in Saxon times, there was even boat building on the banks of Eign Brook.)

It is also possible that the Yazor Brook, which now runs parallel to Eign Brook for part of its course, could have been a tributary of Eign Brook. Yazor Brook had been diverted to power the Eign Gate Mill situated west side of the City on the corner of what is now Bewell and Victoria Streets.

The Eign Mill, clearly a significant mill during the 19th century, was improved in 1814. It had two water wheels powering six sets of French stones, a dressing machine and a bolting mill (used for grading and separating the flour and bran). About this time, the mill was leased by the James family, including Philip Turner James and, from 1830, Isaac William James. We know more about Isaac than the other millers listed in the Littlebury’s directories of this period, because of a collection of documents at Herefordshire Archives and Records Office (HARC) apparently collected by the Trustees of Isaac’s estate. Isaac was parted from his fortune and declared bankrupt in February 1867. His fall from grace was fast. He was listed as miller and maltster in 1830 and in the 1867 trade directory (presumably compiled in 1866) he was a maltster, agent for seeds, manure etc. with offices in Maylord Street. He was also listed as a farmer at Eign Farm at Tupsley. The Bartestree section of the Littlebury directory lists Isaac James as a farmer and hopgrower living at Bartestree Court. He appeared to live well - there is a bill from a Gloucester wine merchant dated 1863 for two dozen bottles of finest claret, costing £4 18 shillings, including carriage to Barrs Court Station.

The cause of his bankruptcy is not known, but he incurred a number of big bills in repairing and upgrading both Eign and Scutt mills, which appear to be steam powered. There are bills dated 1865 for £24 (the equivalent of 140 bottles of finest claret) for repairs to engine and boiler at Eign Mill payable to a Shropshire engineer as well as numerous bills to local metal fabricators.

The conversion to steam and its associated costs were probably forced on Isaac because of increasing competition. The Corn Laws, which limited the import of cheap wheat from the US, Canada and Australia, were repealed in stages from 1846 and, with coming of the railways to Hereford a few years later, would have brought cheaper grain to Hereford where purpose-built steam mills such as the Imperial (below) and two other modern mills, the Victoria and the Hereford, could undercut the domestic product. There are no further references in the trade directories to either Isaac or Eign Mill and the 1888 Ordnance Survey map shows the mill as derelict. It disappears totally in the 1904 edition.

Scutt Mill on Ledbury Road

Imperial Flour Mill, Friar Street

Miller Alfred Watkins from Ron Shoesmith’s book (Logaston Press, 1990)

Miller Alfred Watkins from Ron Shoesmith’s book (Logaston Press, 1990)

Another local flour brand was developed in the 1890’s by miller Alfred Watkins at his mill in Friar Street. He marketed it as Vagos (from the Roman name for the Wye, vaga), not only locally to the city bakers, but nationally through London’s trade fairs. It was a white, malted loaf and when, in 1917, a Harley Street physician declared brown bread a healthier option, Watkins wrote to the Hereford Times: “The instinct of people to select … white bread has been a perfectly sound one.”

The Imperial Mills had been established by Captain Radford as a foundry in 1834. They were purchased by the Berrington Street brewer Charles Watkins, Alfred’s father, in 1876. Alfred modernised the mill, replacing the grinding stone with rolling mills and introducing electric lighting.

The commercial success of the mill and Vagos flour helped fund Watkins’ diverse interests. He devised a bakers thermometer, invented the Bee Photographic light meter, produced an historic collection of photographs and was a significant figure in the Woolhope Club. He died in 1935 and was posthumously celebrated for his theories on ley lines, published in The Old Straight Track.

The Imperial Mills had been established by Captain Radford as a foundry in 1834. They were purchased by the Berrington Street brewer Charles Watkins, Alfred’s father, in 1876. Alfred modernised the mill, replacing the grinding stone with rolling mills and introducing electric lighting.

The commercial success of the mill and Vagos flour helped fund Watkins’ diverse interests. He devised a bakers thermometer, invented the Bee Photographic light meter, produced an historic collection of photographs and was a significant figure in the Woolhope Club. He died in 1935 and was posthumously celebrated for his theories on ley lines, published in The Old Straight Track.

The Bone Mill, Outfall Works Road

The old Bone Mill, situated in the charmingly-titled Outfall Works Road, appeared on the tithe map of 1843 but not, apparently, in any of the directories of the period. The records show that the premises covered a site of 1 acre 3 rods and 9 perches (just under 0.75 hectare). The landowner was John Braithwaite under the Prebend of Bartonsham and the occupier was Thomas Fowler. A rent of £1 1s 6d [£1 7.5p] was payable, split between the Vicar, the Dean and Chapter of Hereford and the Treasurer of Hereford Cathedral.

The site owner in 2016 identified the vestigial signs of the Bone Mill wharf, now only visible when the river is very low. It was from here, in the pre-railway days, that bone meal, a valuable source of fertiliser, started its journey by boat to London.

The owner believes the mill was pony-driven, the animal turning a grinding stone in a stone trough, and that the site was on several levels, descending from the road down to the river bank where the pony laboured.

The site owner in 2016 identified the vestigial signs of the Bone Mill wharf, now only visible when the river is very low. It was from here, in the pre-railway days, that bone meal, a valuable source of fertiliser, started its journey by boat to London.

The owner believes the mill was pony-driven, the animal turning a grinding stone in a stone trough, and that the site was on several levels, descending from the road down to the river bank where the pony laboured.

A former bone mill owner was Ron Spalding. Local resident Tom Wheatstone, a dairyman at Bartonsham Dairy, described using Ron’s services when Black Bess, his float delivery horse, died.

“I went down to the slaughterhouse,” Tom told In Our Age "and Ron was cutting up the horse ready to go on the Paddington Express to London. Dog meat was big business then."

“Joe Bolter, landlord at the Brewer’s Arms, had asked me to bring a couple of steaks off the rump end. So I did. And we had these two steaks, one for me and one for him, in the bar at the Brewer’s. There was Big Reg Griffiths and all the fellows from the sewage works, on their bread and spring onions and cheese, and we had steaks from the horse I’d been stroking earlier in the morning! Very strong.”

“I went down to the slaughterhouse,” Tom told In Our Age "and Ron was cutting up the horse ready to go on the Paddington Express to London. Dog meat was big business then."

“Joe Bolter, landlord at the Brewer’s Arms, had asked me to bring a couple of steaks off the rump end. So I did. And we had these two steaks, one for me and one for him, in the bar at the Brewer’s. There was Big Reg Griffiths and all the fellows from the sewage works, on their bread and spring onions and cheese, and we had steaks from the horse I’d been stroking earlier in the morning! Very strong.”